Updated January 29, 2024

Dementia

What this section covers:

-

The normally aging brain

-

Mild Cognitive Impairment

-

Dementia

-

Medical conditions that can mimic a dementing illness

-

The clinic visit: what to expect

-

Three diseases that cause dementia

-

Alzheimer’s disease

-

Vascular disease

-

Dementia with Lewy bodies

-

-

Key points

The normally aging brain

The adult human brain is about the size of a medium cauliflower and weighs about 3 pounds. It has more than 100 billion neurons and more than 100 trillion connections between neurons (called “synapses”). This is a very complex organ!

In the course of normal aging, neurons are lost, so there are fewer synapses. Some degree of shrinkage (“atrophy”) of the brain occurs.

MRI scans showing atrophy most obvious in the dark, fluid-filled ventricles in the center of the brain. On the left is the MRI of a normal 30-year-old, and on the right is the MRI of a normal 76-year-old. Red arrows point to ventricles.

Blood flow to the brain brings oxygen and nutrients. Any interruption of blood flow can cause “ischemic changes” in the brain’s gray matter and connecting fibers (white matter). These changes can readily be seen on MRI. The MRI scans below show several patterns of ischemic change, indicated by red arrows. Ischemic changes can also be seen on CT scan, but are much better visualized and delineated by MRI scan.

These kinds of ischemic changes in deep white matter can be silent until they accumulate, become confluent, or extend to gray matter. In part, these changes are responsible for cognitive symptoms seen with normal aging.

These cognitive changes include the following:

-

Absent-mindedness

-

Blocking on a name or word

-

Forgetting details

-

Slower processing

-

Changes to “executive functions,” which include planning, organizing, and self-monitoring, among others.

In general, these changes are small and unlikely to interfere with daily function.

A Case

Helen came to the clinic saying she was concerned about her memory. “I saw an old friend, and I’d completely forgotten his name.”

“I see that you’re concerned. When did this happen?” “Last Tuesday. I ran into him in the supermarket.” “Okay. Tell me about it.”

“I was in the produce section at Fry’s looking at tomatoes. He was shopping for applesbecause his wife wanted to make a pie. We had a nice chat about old friends from bowling.”

“So…you remember all those details. Did you ever remember his name?” “Oh, yes. As soon as I got back to my car.”

Do you think Helen should be worried? She had trouble retrieving the name from memory on the spot. She recalled all the details of meeting her friend. Eventually, she recalled his name, as well. The other telltale sign — that this is a normal problem with memory retrieval — is that Helen is concerned. She has plenty of insight and ability to monitor her own situation.

One model of the memory process involves three stages:

-

encoding, in which something (e.g., a shopping list) is memorized

-

storage, in which the list is committed to memory

-

retrieval, in which the list is recalled when needed.

Encoding

Storage

Retrieval

Normal aging can be associated with memory retrieval problems. Some call this “age-associated memory impairment.” This kind of impairment is gradual and relatively insignificant.

Now we’ll move on to talk about brain changes that are not so benign.

Look at the graph shown below. The top line (in green) shows the progression of cognitive decline in normal aging. As you can see, there is not much decline, even as the line extends into old age. The lower line (in green-yellow-orange) shows what could happen if changes in the brain begin to show up as changes in mental abilities and activities of daily living. The curve falls off, first reflecting a condition called mild cognitive impairment.

Mild Cognitive Impairment

(Mild Neurocognitive Disorder)

If you were to come to the clinic for a memory evaluation, you would be asked a series of questions about what you’ve noticed regarding your memory and other mental abilities. In addition, an informant who knows you well enough to answer the same questions would be asked. You would also answer questions from a “screening” cognitive testing instrument such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment or the Mini Mental State Exam, pictured below.

Mild cognitive impairment is characterized by the following:

-

Mild decline in cognitive function

-

Modest impairment in cognitive testing

-

Preserved ability to perform activities of daily living (although may need to use aids and reminders more than usual)

More detailed information could then be obtained from a longer session of testing done by a neuropsychologist, a specialist in this type of testing.

Dementia

(Major Neurocognitive Disorder)

If the memory evaluation shows more severe problems, a diagnosis of dementia might be made. This steeper decline of (clinical) dementia is also shown in the graph above.

Dementia is characterized by the following:

-

Significant decline in cognitive function

-

Substantial impairment in cognitive testing

-

Impaired ability to perform activities of daily living

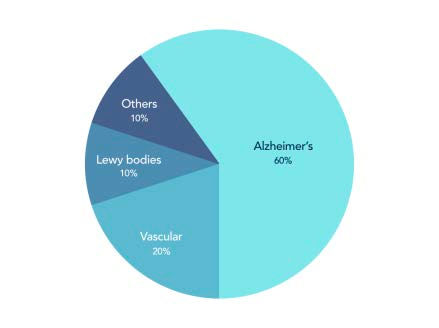

What causes mild cognitive impairment and dementia? The most common cause is Alzheimer’s disease. Vascular disease of the brain with or without Alzheimer’s disease is the next most common. Dementia with Lewy bodies is third most common. There are also many other potential causes.

Medical conditions that can mimic a dementing illness

Certain medical conditions can affect cognition the extent that the patient “looks like” they have Alzheimer’s disease or another true dementia.

These conditions include:

-

Vitamin B12 deficiency

-

thyroid illness

-

liver disease

-

neurosyphilis

-

major depression

Many of these conditions can be treated, such that over time, memory and other cognitive functions can improve.

Certain medications can also cause memory and other cognitive problems, and this could be mistaken for true dementia. These drugs include:

-

opiates (e.g., Demerol, codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone)

-

benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium, Ativan, Xanax)

-

Benadryl (diphenhydramine) and other strongly anticholinergic drugs (e.g., Vistaril, amitriptyline, high-dose doxepin)

-

over-the-counter sleep aids (e.g., Unisom, doxylamine)

The clinic visit: what to expect

In addition to questions about memory and other cognitive abilities in daily life, the evaluation includes questions about the following:

-

Medical history

-

Current medications (including over-the-counter drugs)

-

Daily function

-

Changes in mood or personality

The evaluation would also include:

-

Cognitive testing (MOCA, MMSE, neuropsychological testing)

-

Physical examination

-

Laboratory studies

-

Brain scan (MRI or CT)

Review of the findings from this evaluation would address these questions:

-

Is there a reversible condition that can be treated?

-

How severe is the impairment: is it MCI or dementia?

-

What is the likely cause: is it Alzheimer’s disease or something else?

Early diagnosis is important because early treatment is more likely to preserve brain function.

In addition, early diagnosis helps you and your family make plans, and may connect you with those performing clinical treatment trials.

Now we’ll move on to talk about the three most common diseases associated with dementia in elders:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

-

vascular dementia

-

Dementia with Lewy bodies.

A Cautionary Note

It is NOT enough to be given a final diagnosis of “dementia.” That would be like bringing your child to the emergency room and having them say, “Well, your child has a fever and chills.” What’s the first thing you want to know? You want to know why, right? What’s causing the fever and chills? In the same way, you want to know what disease is causing the dementia. In many respects, the treatments for different causes of dementia are different.

Alzheimer’s disease

(Major neurocognitive disorder due to AD)

The slide to the right shows a sample of brain tissue with two changes that are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease (AD):

-

Plaques (labeled NP for neuritic plaques)

-

Tangles (labeled NFT for neurofibrillary tangles)

Plaques are beta-amyloid protein deposits outside the nerve cells that are an early finding in AD. A great deal of research and clinical effort has focused on preventing or ridding the brain of these deposits.

Tangles are abnormal accumulations of tau protein inside neurons that disrupt the work of the cells. Tangles develop later in the progression of the disease, and are more closely associated with cognitive decline.

Atrophy (shrinkage) of the brain also is seen. Earlier, we saw several MRI scans, of a normal 30-year-old and a normal 76-year-old. The scan at the left shows the brain of a 75-year-old with AD. Note the much greater enlargement of the central ventricles and other fluid-filled spaces.

Clinically, Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the following:

-

Memory problems early in the course

-

Gradual onset

-

Slow progression

-

Normal physical examination

-

Poor insight

-

MRI or CT that is normal in early stages

The fact that the physical exam is normal for years in AD means that the disease might not be noticed until later stages. Casual observers might think there is nothing wrong. Even when it becomes obvious to family members and more observant friends that there is a problem, the patient might insist that there is nothing wrong. This is what is meant by poor insight.

What this often means is that the family ends up dragging the patient to the clinic against their will. The patient often does not recall episodes of forgetting. This can make it very difficult to complete a diagnostic work- up and provide treatment. A private talk with clinic staff before the appointment can help smooth this process.

Clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease

Memory problems

Here’s something we often hear in the clinic: “I know there’s nothing wrong with my husband’s memory. He remembers every single student in our high school. In fact, he remembers our first date better than I do.” In response, we explain that, because memory encoding is a problem in AD, and because her husband didn’t have dementia with encoding problems until later in life, his memory for distant events is much better than his memory for recent events. He might remember high school just fine, but can’t remember what he had for breakfast or whether he’s taken his pills.

Language problems

Language problems in AD take the form of substituting words (using the wrong word) or “talking around” lost words to avoid using them. Eventually, the patient with AD becomes quiet.

Decline in judgment

Judgment is one of the executive functions of the brain, prominently involving the brain’s frontal lobes. Loss of judgment can be dangerous when the individual is still driving a car or operating appliances. Among other problems, those with poor judgment are susceptible to fraudsters who call on the phone or appear at the door, asking for personal financial information.

Changes in mood or behavior

Alzheimer’s disease can be associated with depression, anxiety, changeable mood, anger, or striking-out behavior.

Functional decline

With the transition from MCI to dementia, the individual is unable to function as usual in daily life.

The change starts with higher-level activities like driving and writing checks, and then progresses to lower-level activities like making coffee and personal grooming.

Can Alzheimer’s disease be prevented?

Although vaccines are not clinically available for AD, risk can be reduced by addressing modifiable risk factors. Known risk factors for developing AD include the following:

-

Old age

-

High blood pressure

-

Diabetes

-

Hyperlipidemia (high cholesterol and other bad lipids)

-

Sedentary lifestyle

-

Unhealthy diet

-

Social isolation

-

ApoEe4 genotype

-

Family history of AD

Modifiable risk factors are shown in bold. Most of these risk factors show themselves by middle age. Risk can be reduced! The section on Brain Fitness deals with this in more detail.

Treatment of Alzheimer's disease

Treatments for AD have been a very high priority on the research agenda for many years, both at NIH and in the pharmaceutical private sector. Scores of drugs and brain stimulation therapies have been aggressively studied, including amyloid vaccines, tau vaccines, immunotherapies, diabetes drugs, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and deep brain stimulation. News about these treatments is often positive initially, but too often, the results from later Phase III studies and post-marketing experience turn out to be discouraging.

Drugs with FDA approval for AD treatment include the following:

Cholinesterase inhibitors:

-

Donepezil (Aricept)

-

Rivastigmine (Exelon)

-

Galantamine (Razadyne)

NMDA receptor antagonist:

-

Memantine (Namenda)

-

Also available in combination with donepezil (Namzaric)

The newest treatments for AD are immunotherapies, which appear to show particular promise when used in combination with focused ultrasound to open up the blood-brain barrier for drug delivery to the brain. As of early 2024, three new immunotherapies have been developed:

-

Aducanumab (Aduhelm)

-

Lecanemab (Leqembi)

-

Donanemab, which is awaiting approval by the FDA (as of March 2024)

The three drugs work on different stages of amyloid plaque formation. The drugs are given by IV infusion under clinical supervision. Drug approval for aducanumab was highly controversial, and Biogen has announced that it will discontinue this drug in 2024.

Vascular Dementia

(Major Neurocognitive Disorder due to Vascular Disease)

Anything that restricts blood flow to the brain has the potential to cause vascular dementia. Larger insults like strokes can cause major injury, with dementia as an immediate consequence. Smaller insults from conditions such as untreated atrial fibrillation can cause tiny injuries that may accumulate over time. The slide at right shows a section from a brain with vascular changes associated with atrial fibrillation. When a tiny clot travels to a deep penetrating artery of the brain, a lacune may form. Lacunes can be clinically silent or be associated with specific clinical syndromes, depending on variables such as size and location.

Brain MRI with arrows indicating tiny holes called lacunes.

Vascular dementia can co-occur with Alzheimer’s disease (mixed dementia), and the combined disease appears to be more common than previously believed.

When vascular dementia occurs in isolation, it looks different from Alzheimer’s disease from a clinical standpoint.

Pure vascular dementia is characterized by the following features:

-

The onset of dementia can be acute with a major stroke.

-

The decline can be stepwise with minor infarcts.

-

Physical examination is not normal, even in early stages.

-

MRI or CT of the brain is abnormal.

-

The patient has problems with walking, articulating speech, and swallowing.

-

Poor posture is common.

-

Urinary incontinence is very common.

-

Depression is common.

Treatment of vascular dementia

This is one type of dementia for which surgery may be an option. If one of the carotid arteries feeding the brain is blocked (usually by atherosclerotic plaque), then carotid endarterectomy or angioplasty may be indicated.

Other treatments are the same as those for treating heart disease:

-

Blood pressure control

-

Cholesterol management

-

Blood thinners

-

Smoking cessation

-

Moderation of alcohol use

-

Weight loss, if indicated

-

Avoidance of inactivity

In addition, there may be a modest benefit from the drug memantine (Namenda) for brain protection in vascular dementia.

Dementia with Lewy bodies

(Major neurocognitive disorder with Lewy bodies)

Clinically, this disease can look like a combination of Parkinson’s disease and dementia. The order in which symptoms develop is the key to diagnosis.

When dementia develops after Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms are established, it is called Parkinson’s disease with dementia.

When dementia develops first or at the same time as motor symptoms, it is called dementia with Lewy bodies.

This slide shows a Lewy body, the round, dark pink inclusion inside the neuron that is characteristic of

both dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease.

In some cases, progression of dementia with Lewy bodies calls attention to itself by its strange symptoms, including prominent dream-enactment behaviors, vivid visual hallucinations, and episodes of unresponsiveness that come and go as if turned on and off by a switch.

Dream enactment — REM sleep behavior disorder — may involve violent movements in bed that can injure the patient or (more often) their bed partner. REM sleep behavior disorder can precede the appearance of dementia with Lewy bodies by many years.

Visual hallucinations are notable for their color and detail. These visions may take the form of tiny, colorfully dressed people; these have been called “Lilliputian” hallucinations, after the small inhabitants of the island visited by Gulliver in his travels.

Episodes of sudden unresponsiveness lasting up to 10 minutes are frightening for bystanders and are still incompletely explained.

Core features of dementia with Lewy bodies include the following:

-

Dementia

-

Fluctuating cognition (especially attention and alertness)

-

Well-formed visual hallucinations

-

REM sleep behavior disorder

-

Parkinsonism

Other symptoms include extreme sensitivity to antipsychotic drugs, postural instability, repeated falls, “fainting” episodes (syncope), constipation, urinary incontinence, blood pressure drop on standing, excessive sleepiness, loss of the sense of smell, non-visual hallucinations, delusions (false beliefs), apathy, anxiety, and depression.

Dementia with Lewy bodies can be distinguished from other dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease with a SPECT (or PET) scan visualizing the dopamine transporter, a protein that drives dopamine across the cell membrane for reuptake into the cell. This is called a DAT scan.

Treatment of Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)

-

Cholinesterase inhibitors can help with cognition, sometimes dramatically.

-

Parkinson’s disease medications such as levodopa/ carbidopa (Sinemet) have modest effects on motor symptoms in DLB.

-

Hallucinations can be treated with atypical antipsychotics such as quetiapine, but the novel antipsychotic pimavanserin may be preferred for this indication.

-

Deep brain stimulation to the nucleus basalis of Meynert has shown promise in a small number of patients in reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies.

Key points

-

The normally aging brain may show a small degree of atrophy and ischemic change associated with minor symptoms such as absent- mindedness and occasional blocking on a word. Most memory problems have to do with retrieval.

-

Mild Cognitive Impairment — a mild decline that shows up in testing to a modest degree. No problems with activities of daily living.

-

Dementia — a significant decline that shows up in testing to a substantial degree. Impairment is seen in activities of daily living.

-

Medical conditions that can mimic a dementia include Vitamin B12 deficiency, thyroid disease, major depression, and the use of certain medications.

-

The three most common diseases that cause dementia in elders are Alzheimer’s disease, vascular disease (with or without Alzheimer’s disease), and dementia with Lewy bodies.